The Dynasty That Didn't

Asking the question: What if the 1988 Mets had stuck the landing? An exploration of key figures from the mid-to-late ’80s Mets on the field, in the dugout and in the front office.

The 1986 Mets are as famous for their excellence as they are notorious for their brashness.

The Davey Johnson-managed team cruised to 108 wins and won a classic World Series in seven games against the Red Sox.

The 1988 Mets were just as dominant as the ’86 squad during the regular season, but what that successor lacked was a satisfying denouement to its season. That lack of resolution is why the 1988 team is overlooked today as one of the most complete teams of the Expansion Era.

“We had a better team talent-wise in ’88 than we had in ’86,” former Mets right fielder Darryl Strawberry said this fall on the podcast “Amazin’ Conversations With Jay Horwitz.”

Consider the following. The 1988 Mets:

• Won 100 games

• Led the National League with 703 runs scored

• Allowed 532 runs, the fewest in the NL

The 1988 Mets didn’t just outplay NL competition. They dominated it.

As a team, New York batters hit 30 more home runs than the No. 2 Reds, who had Eric Davis, Paul O’Neill and Barry Larkin in their primes. Mets pitchers struck out 51 more batters than the Nolan Ryan-led Astros.

The 1988 Mets had starpower. The club featured all-star seasons from right fielder Darryl Strawberry, catcher Gary Carter and starting pitchers Dwight Gooden and David Cone. First baseman Keith Hernandez won his 11th and final Gold Glove.

Strawberry finished second in MVP voting and left fielder Kevin McReynolds finished third. Cone finished third in Cy Young Award voting and 10th in MVP voting. Randy Myers saved 26 games and received MVP votes.

So why is this team largely forgotten today?

They didn’t stick the landing.

“The ’88 team didn’t have the heart and the guts like the ’86 team . . .” Strawberry continued on his podcast appearance. “You had to have a different personality, a different swagger about yourself like the ’86 team.”

The favored Mets lost to the Dodgers in seven games in the 1988 NL Championship Series, blowing a golden opportunity to authenticate their 1980s run as a dynasty.

Had the Mets added a second World Series ring in the span of three seasons, how much differently would their 1980s clubs be remembered today?

That’s the “what if?” question that came to mind when I wrote Davey Johnson’s obituary for Baseball America in September.

If not for one magical pitching season from Dodgers ace Orel Hershisher—in the 1988 NLCS he pitched to a 1.09 ERA in 24.2 innings with a win and a save in four appearances—or one unlikely Game 4 home run from Mike Scioscia against Gooden, how would the mid-to-late ’80s Mets be remembered today?

Let’s speculate!

Davey Johnson would be in the Hall of Fame

Note: Parts of the following entry are reprinted from my Baseball America obituary for Johnson in the October 2025 issue

The Mets hired Johnson to manage their Double-A Jackson affiliate in 1981. He moved to Triple-A Tidewater in 1983 and then up to New York in 1984. As good as he was as a player—he won two World Series with the Orioles, made four all-star teams and won three Gold Gloves—Johnson is most famous for his time as Mets manager.

In seven seasons in Queens, he guided the Mets to a .588 winning percentage, including 108 wins and a World Series championship in 1986. From 1984 to 1990 the Mets had 666 wins, the most in MLB.

What distinguished Johnson as a manager was his embrace of data and creativity—spurred by watching Earl Weaver in Baltimore—as well as his reputation as a player’s manager, which often put him at odds with management, in New York and beyond.

Johnson continued to find success after the Mets fired him in 1990. He also led the Reds, Orioles and Nationals to the playoffs, just as Billy Martin led four different teams to October. Only Dusty Baker, with five, has a higher total.

Johnson managed one World Series champion and six total playoff teams—just as Weaver had on both counts—while finishing with a .562 winning percentage that ranks 15th highest among managers with at least 1,000 games. Everybody ahead of him on the list is in the Hall of Fame, except 19th century manager Jim Mutrie and active managers Dave Roberts and Aaron Boone.

A second World Series ring would have made Johnson’s achievement that much clearer.

Keith Hernandez would be a stronger Era Committee candidate for the Hall of Fame

Many of the core players on the 1986 and ’88 Mets were the same, highlighted by position players Keith Hernandez, Darryl Strawberry, Gary Carter, Lenny Dykstra and Wally Backman and pitchers Dwight Gooden, Ron Darling, Sid Fernandez, Bob Ojeda and reliever Roger McDowell.

Carter is the only 1986 Mets player in the Hall of Fame, which is difficult to believe for a club that won the most games in MLB for a seven-year stretch surrounding its championship season.

Had the Mets won the World Series two times in three years, would that still be the case? And if another 1986 Mets player should be in Cooperstown today, who would be the pick? Mine would be Hernandez.

Strawberry and Gooden had Hall of Fame peaks but faded at young ages as they grappled with drug and alcohol addiction. Strawberry held the Mets franchise record with 252 home runs until Pete Alonso broke it in 2025. Gooden won the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Award in successive seasons, something only he and Paul Skenes have ever done.

Hernandez battled his own demons, but he had a longer peak than Strawberry or Gooden. He also racked up several key achievements that HOF voters like to see, such as a 1979 National League co-MVP award, a record 11 Gold Gloves at first base and black ink for key categories such as runs, doubles, walks, batting average and OBP.

Oh, and he has two World Series rings, the first with the 1982 Cardinals.

Many credit Hernandez with helping the talented but undisciplined Mets find their footing and take the final step toward contention when he was acquired to be team leader midway through the 1983 season.

And contend the Mets did. They had the youngest team in the NL in 1984. They won 90 games that season and then 98 the next. In 1986 the Mets hit their stride, winning 108 games and the World Series, and they followed that with 92 and 100 wins.

All those wins in the regular season resulted in just two postseason appearances. That was life before the wild card.

But as to Hernandez, it surprises me that his Hall of Fame case has not picked up more steam in the analytics age. While he hit just 162 home runs and never reached 20 in a season, he owns a career .384 OBP and 128 OPS+.

From 1970 to 1995, only Rod Carew and Eddie Murray generated more bWAR among first basemen (min. 1,000 games at the position) than Hernandez, who had 60.4, owing largely to his on-base skills and historic fielding ability.

Hernandez was not completely overlooked by the writers. He hung around for nine HOF ballots before falling below the 5% threshold in 2004. I think his case should be reexamined.

David Cone’s Cooperstown case would be embellished

Later in his career, Cone was regarded as a wily veteran who changed speeds and varied his arm angle, but as a youngster he was a power pitcher who had one of the best sliders in baseball.

In Baseball America Best Tools voting, only John Smoltz, Randy Johnson, Chris Sale and Max Scherzer have received more notice for Best Slider than Cone.

A 25-year-old Cone burst on the scene in 1988 by going 20-3 with a 2.22 ERA and 213 strikeouts. Later, he led the National League in strikeouts in 1990 and 1991. The Mets traded him to the Blue Jays at the 1992 deadline, and he helped pitch Toronto to a World Series title that year. He later won rings with the Yankees in 1996, 1998, 1999 and 2000.

In total, Cone went 12-3 in 21 career postseason appearances, with a 3.80 ERA in 111.1 innings.

Naturally, he was excellent in the regular season, too. Cone won 194 games in 17 seasons, compiling more than 60 WAR (a top 10 total for eligible non-Hall of Fame pitchers) with a 3.46 ERA and 2,668 strikeouts in 2,899 innings.

He appeared on the 2009 Hall of Fame ballot but fell off after receiving just 3.9% of the vote. It’s fair to wonder what having a sixth ring with the 1988 Mets as a headlining starting pitcher—for a third different World Series champion!—would do for Cone’s Hall of Fame case.

Frank Cashen would be a celebrated executive

The Mets and Orioles met in the 1969 World Series.

Linkage existed between the two organizations for decades after the Miracle Mets won their first championship.

Baltimore had a true dynasty in the 1960s and early ’70s. It won the 1966 and 1970 World Series and claimed American League pennants in 1969 and 1971. The Orioles won with Hall of Fame talent, including Frank Robinson, Jim Palmer and Brooks Robinson, and a strong supporting cast.

A key member of Baltimore’s supporting cast was all-star second baseman Davey Johnson. He would later become a key figure in Mets franchise history.

Johnson managed the Mets to prominence after he took over in 1984. He had powerful allies in the Mets’ front office. Like Johnson, general manager Frank Cashen and scouting director-turned-assistant-GM Joe McIlvaine were part of the Orioles’ dynasty.

Cashen headed baseball operations in Baltimore from 1965 to 1975, while McIlvaine was an Orioles scout in the 1970s. Cashen, Johnson and McIlvaine later reunited in New York to play key roles in building and steering the Mets to contention in the 1980s.

Cashen is not talked about much today as an all-time executive, but his track record with the Orioles and Mets is difficult to ignore. His Orioles clubs cultivated a strong base of talent in the pre-draft and pre-free agency era, while his Mets clubs navigated both challenges to build a consistent winner.

The Mets under Cashen nailed high first-round picks in Darryl Strawberry (No. 1 overall in 1980) and Dwight Gooden (No. 5 overall in 1982). New York under Cashen drafted contributing players Lenny Dykstra, Roger McDowell, Randy Myers and Rick Aguilera. It signed Kevin Mitchell as an undrafted high school player. Cashen also drafted future two-time Minor League Player of the Year Gregg Jefferies in 1985.

Cashen traded for MLB veteran leaders Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter. He also traded for David Cone, Ron Darling, Sid Fernandez and Howard Johnson before they were established big leaguers.

So why is Cashen not as well known today? Much like the 1988 Mets team he built, his final act in Queens had an unsatisfying denouement.

In the years following the 1986 championship, Cashen traded away Dykstra, Mitchell, McDowell and several popular Mets players in unpopular trades that yielded underwhelming returns. On top of that, star prospect Jefferies failed to develop in New York prior to his trade in December 1991. Strawberry walked as a free agent after the 1989 season.

And then there was the Mets’ front office line of succession.

According to authors Bob Klapisch and John Harper in their 1993 book “The Worst Team Money Could Buy,” Cashen let his ego get in the way not only of player personnel decisions outlined above, but also when it came to the club’s transfer of power in the GM chair.

McIlvaine was considered to be next in line, but he got tired of waiting and took the Padres’ GM job in 1990 as Cashen clung to power in New York. That left assistant GM Al Harazin as the next man up for the Mets late in the 1991 season.

Harazin’s ascension to GM—he had made his name not as an evaluator but as a contracts expert—presaged a dark period for the franchise. The 90-loss 1993 team, immortalized by Klapisch and Harper in their book, was typified by high-profile Harazin moves that backfired, including the acquisitions of Bobby Bonilla, Bret Saberhagen, Vince Coleman and Eddie Murray.

The 1980s Mets would be regarded as a dynasty

Strawberry was only exaggerating slightly when he said the 1988 Mets were more talented than the ’86 champions.

Both teams are among the most dominant regular-season teams of the Expansion Era. Both were true-talent 100-win juggernauts that dominated the National League on both sides of the ball.

Both teams led the NL in runs scored, despite playing half their games in Shea Stadium, an extreme pitcher’s park.

Naturally, the pitchers thrived at Shea, and the 1988 staff allowed just 0.49 home runs per nine innings. That is one of the lowest rates of the past five decades over a full 162-game season. Only the 1984 Dodgers and 1980 Astros were lower since 1980.

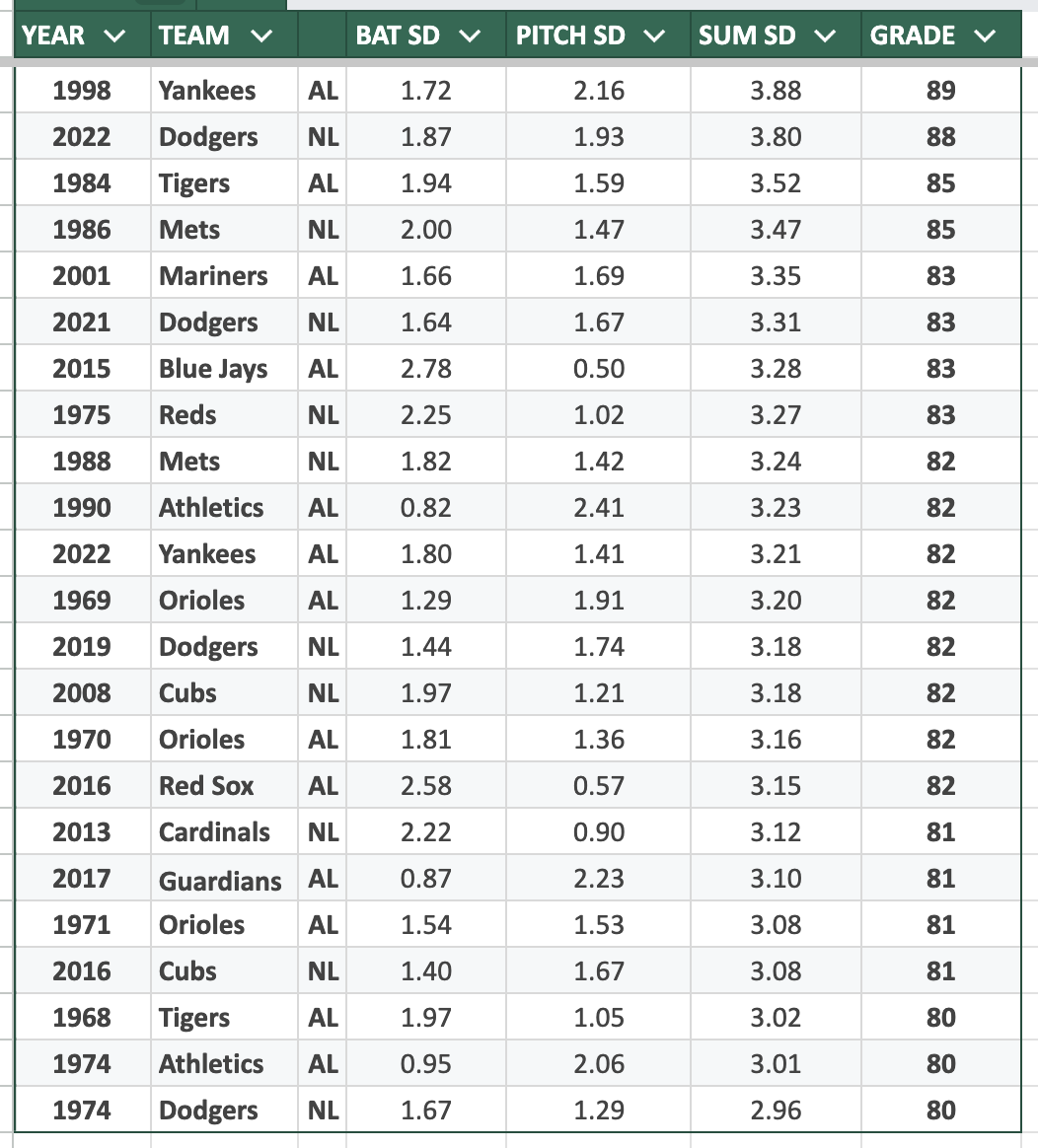

We can get a sense for the magnitude of a team’s dominance by applying a standard deviation Z-scoring to their totals of runs scored and runs allowed. Authors Rob Neyer and Eddie Epstein relied on the method for their 2000 book “Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams Of All Time.”

The reason that the Z-score method works, as does run differential or Pythagorean record, is that it neutralizes park effects. A Mets team playing in Shea Stadium in the 1980s will be aided in run prevention just as much as it is hampered in run creation.

Neyer and Epstein presented their results in terms of standard deviation scores, or SD scores. For example, summing the 1986 Mets’ runs scored and runs allowed SD scores yields a team total of 3.47. By this method, the 1986 Mets were collectively about three and a half standard deviations above average, which is the fourth-highest total of the Expansion Era.

But because a 3.47 SD score is not an intuitive way to think about team quality, I like to map those scores to the 20-80 scouting scale. Doing so reveals that the 1986 Mets scored at a scale-busting 85. The 1988 Mets scored at 82. Both figures are among the highest of the Expansion Era.

The table below contains all the teams to score at 80 or higher in a 162-game season during the Expansion Era.

This list captures a representative cross-section of the most dominant teams of the past 65 seasons, with only a few head-scratchers. The 2015 Blue Jays? The 2008 Cubs? The 2016 Red Sox but not the 2018 champions? Otherwise, the list is chock full of champions, pennant winners and 100-game winners.

If we expand the sample to include the top averages for spans of at least five seasons, we find that Mets runs ending in 1990 (77) and 1989 (76) are among the best of the Expansion Era.

The only teams ahead of them are Dodgers’ five-year samples ending in 2022, 2023, 2021, 2024 and 2025 as well as the 1969–1973 Orioles. That’s it.

Here are the best stretches of at least five seasons for teams during the Expansion Era, sorted into 80, 75 and 70 tiers.

80 Tier

• 2015–2025 Dodgers (11 seasons)

75 Tier

• 1966–1974 Orioles (9 seasons)

• 1984–1991 Mets (8 seasons)

70 Tier

• 1970–1976 Athletics (7 seasons)

• 1972–1977 Reds (6 seasons)

• 1994–2002 Yankees (9 seasons)

• 1974–1978 Dodgers (5 seasons)

• 2015–2023 Astros (9 seasons)

• 1976–1980 Yankees (5 seasons)

• 1991–1999 Braves (9 seasons)

• 2007–2011 Phillies (5 seasons)

• 2001–2005 Cardinals (5 seasons)

• 1983–1987 Tigers (5 seasons)

Right away, the key separator is obvious. The 2020s Dodgers, 1970s Athletics and Reds and late 1990s Yankees all won multiple World Series. The Mets won only in 1986 and squandered a golden opportunity in 1988.

It all circles back to the unsatisfying conclusion. Had the Mets won the 1988 World Series, then the mid-to-late ’80s clubs would be regarded as one of the great dynasties of the Expansion Era.

I mean the '88 World Series ended up giving us one of the most memorable postseason moments ever, but an A's/Mets World Series would have been a battle of juggernauts.

Good stuff Matt! The ‘88 Dodgers are sooo fluky, and Hershiser frankly deserves HOF consideration as well, I always considered him and Cone to be quite similar. Cone dominated more but Orel was a horse, huge IP totals.